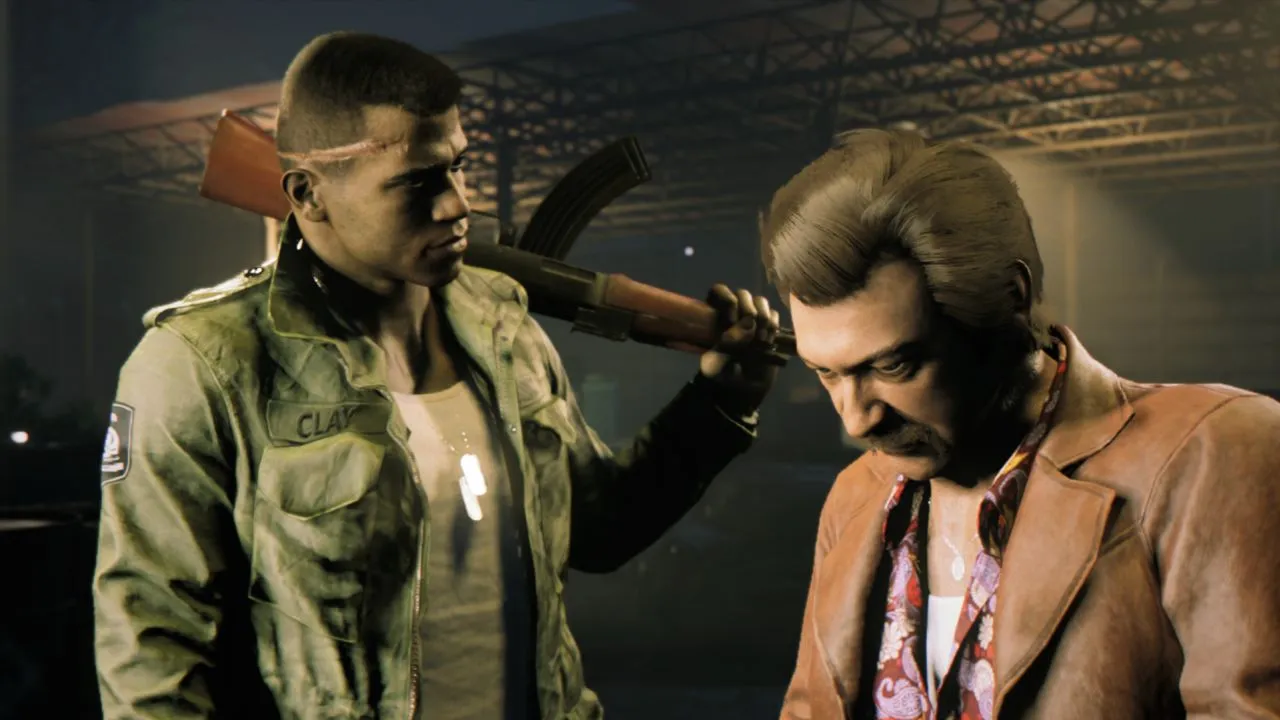

Mafia III Review

Mafia III is a fascinating period-piece game set in 1968, a year

often cited as one of the most turbulent times in American history. The

Vietnam War, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F.

Kennedy, the civil-rights movement, the women’s-rights movement, rioting

in more than 100 cities – many of these historical moments are used to

shape Mafia III’s world, even though it takes place in a fictional

version of New Orleans called New Bordeaux. Developer Hangar 13 doesn’t

shy away from the controversial content, and instead shines a spotlight

on it, giving gamers an intimate look at an unstable Deep South, where

racism and a tense feeling of hatred are ever present.

There is

no tactful way to handle racism – it’s always ugly – and it’s ugly in

this game as well. Hangar 13 wants players to feel the full effect of

it, and that message is delivered loud and clear in Mafia III, seen from

the eyes of Lincoln Clay, a biracial character who we meet moments

after he returns from the Vietnam War. Although Clay served his country,

he isn’t seen as a hero or a person deserving respect. He is instead

viewed suspiciously; women clutch their purses around him and tell him

to walk on the other side of the street. He’s also called the n-word

repeatedly. Finding yourself standing in a world that has an

institutional bias against you is uncomfortable, and I think Hangar 13

does an admirable job of trying to make players think about these

issues. They are constants for the 30-plus hours it takes to complete

the game. However, what begins as a unique and powerful backdrop for a

game quickly becomes a typical revenge story that could unfold anywhere

with anyone standing in as the protagonist.

The

first two hours of Mafia III are special – a linear narrative with

teeth destined to tackle the issues of the day head-on. The events are

told through alternating timelines; one following Clay’s exploits,

another set years later through the lens of a faux-documentary told from

the perspectives of people who witnessed the events firsthand. As

predictable as this journey becomes, the writing is top notch and is

used to paint a wonderful cast of characters, who are sadly lost amid

the bloodshed and one-note narrative approach that becomes the central

focus.

The trouble for Clay begins when he agrees to help the

Italian Mob rob a bank. The elaborate operation is cool to be a part of

and pays off handsomely in the end. The Italians get a huge cut, and

Clay gets enough to take care of him and his family for life. It’s a

moment to celebrate – a beautiful sequence – that ends in disaster. The

Italians had no intention of giving Clay or his people anything; they

were viewed as disposable parts of this job. Clay, his surrogate father,

and everyone he loved are mowed down. Clay takes a bullet to the head,

but somehow survives. From the moment he awakens, he wants nothing but

revenge. It’s a powerful motivator, but ends up dominating the remainder

of the story, and is told in a way where we don’t learn much more about

Clay until the end of the game. He becomes a faceless drone focused

solely on bloodshed.

Clay wants to make the head of the Italian

Mob, Sal Marcano, feel a great sense of loss. To accomplish this feat,

he needs to take down Marcano’s operations piece by piece. This is where

Mafia III falls apart, and not just narratively. Players are subjected

to an open-world gameplay design that favors repetition above anything

else. The world itself is vividly realized, and fun to soak in – whether

it’s the gator-infested swamps, or streets filled with drunkards during

a Mardi Gras celebration – but there isn’t much to do other than

approach a racket (usually consisting of a handful of enemies and

something to destroy) and take care of business. The rackets range from

drug trafficking and money laundering to, well, the Klan auctioning off

people of color. No matter what racket you gun for, they all play out

the same way – kill everyone. Even when tasked to interrogate the

target, the best approach is to gun them down, so they take a knee and

can’t flee. These rackets fall quickly, but to reach the boss at the top

of their respective food chain, you need to whittle away at their

operations, and that process grows duller as the game unfolds.

These

actions legitimately feel like work at times, and there’s the

oft-chance that two consecutive racket missions may take place in the

same location, with the same enemy formations. Clay’s approach to these

situations is crude and simple: sneak in, knife or knock out as many

people as possible (through solid stealth controls), and bring out the

guns should they see you. Despite the targeting reticle being the size

of a beach ball (making headshots dubious at times), the gunplay is fun

and intense. Enemy A.I. is fairly easy to exploit, but they also don’t

miss and can put you on the brink of death in a second. The thrills,

which could have been large, are sapped by the repetition of scenario

designs. All of the rackets bleed together into one long, nightmarish

mission that appears to be here just to halt story progress. Even the

divvying up of funds to mob bosses to earn character-based benefits, such

as extra health bars or explosives at the store, falls apart as the game

unfolds.

The Mafia games of old were criticized for barren open

worlds, and the rackets seem like a response to that, but they only slow

the experience down to an uneventful crawl. The only missions that

truly shine are the story-intensive ones centered on taking down

Marcano’s top lieutenants. A boxing match is used in a clever way (and

has an awesome outcome), and LSD is used to hilarious effect at the wake

of one of Marcano’s men. Mafia III is at its best when its focus is on

linear gameplay design – like the previous two games.

The open world is mostly wasted. Driving

is often used to shuttle Clay from location to location (thanks largely

to the game NOT having fast travel). The best diversion is breaking into

people’s homes to steal an album or an issue of Playboy, Hot Rod, or Repent Magazine. The Playboys

are actual issues from the 1960s, and feature small samplings of the

content. Yes, that mostly means nudie pictures, but you also get

articles, such as a 14-page interview with Eldridge Cleaver, the leader

of the Black Panthers. I sadly learned more about the time through Playboy than the game’s story.

Mafia

III is a missed opportunity to explore an important time in American

history, and ends up being one of the most lifeless and

one-note open-world experiences I’ve come across. You can see the

potential for a great game here, but it sticks to safe and simple

gameplay and storytelling conventions, and ends up being a bloody bore.