Please support Game Informer. Print magazine subscriptions are less than $2 per issue

Warren Spector 'Pretty Psyched About Games Right Now'

During Gamescom, we had the opportunity to sit down and talk with Junction Point's Warren Spector for a while. During our conversation, a variety of subjects popped up, including his thoughts on the 3DS ("I’m even more excited"), the current state of the industry ("I think we’re actually living in somewhat of a golden age in games right now"), and, of course, Epic Mickey.

In addition to his love for the character, we learned about how Spector thinks his work on games such as Deus Ex and the Ultima series has given him an advantage on this project, and found out what about what he's proudest about with the game. (It's a bit more surprising and significant than "It's fun," too.)

Q: Right after E3, you blogged about the 3DS and you seemed quite excited about it. Now that you’ve had time to process what you saw with that technology and presumably have had more time with it, have your opinions solidified?

Warren Spector: I’m as excited about that device as I was at E3. If anything, I’m even more excited. True 3D with no glasses, great visual quality, adjustable so every human can see 3D—c’mon, it’s a fantastic little thing. I go on Amazon pretty much every day just to see if they’re taking preorders yet. The day they do, I’m clicking “buy.” I love the thing. I think it’s great.

Q: As a game designer, how do you approach 3D? What does that allow you to do—theoretically, of course—that you can’t do otherwise on traditional displays? Is it just a nice visual bonus, or can you do things mechanically that would be impossible before?

Spector: The coolest thing about the 3DS and about stereoscopic 3D without glasses is that I have no idea what I would do. I would never say that game development is a solved problem. With movies, the position of the sprocket wheels hasn’t changed for 100 years, right? Making movies is a solved problem; it’s just about creating compelling content. Game design and development is not yet a solved problem, but it’s pretty close. I pretty well know how to start, what kinds of games I want to make, kind of how to make them, and how long it takes, and what sort of people you need. And then I think about what impact is stereoscopic 3D going to have on what I do for a living, and I go, ‘No idea.’

So the coolest thing to me is that all of a sudden there’s a new kind of challenge that I have no idea about. Any developer who’s saying, ‘Oh yeah, I’m working on a 3DS title and I know how to do it—I’m making a flight sim where it looks like you’re really flying,’ it’s like, OK, you haven’t thought hard enough. There’s more that we can do with the 3DS than just saying, ‘Oh look, there’s a crate between me and my target.’ There’s got to be. But what it is, I have no idea—and that’s exactly why I would love to just have six months, a year to just play with the 3DS and see just what the heck it does afford you and how it does change game design.

Q: Epic Mickey seems to be getting the attention of people who normally aren’t into video games...

Spector: That was one of the things that really attracted me to this project For years, I’ve been making these games that were about offering the player choices, they decide how to deal with those choices, and we show the consequences of their choices. I’ve always thought that was really sort of a mainstream idea, that normal people—nongamers—should have a chance to experience that. This is not just, ‘Jump, jump, jump, step on the giant’s toe, he opens his mouth, you throw a rock in it, and you beat the boss.’ That’s a pretty gamer sort of thing to do. In almost any game, if you’re not skilled enough or smart enough to do what the designer wanted you to do, your only option is to stop playing. In the games that I make, those games of choice and consequence, if solving the problem one way doesn’t work, try solving it another way, and if that doesn’t work, try solving it another way. Just do what you think is fun, and the game will support that. I always thought that was a mainstream idea, but for some reason it’s never actually gotten out to the mainstream. Now, with Mickey as my hero, I think I can actually get that idea into the hands of your readers, and I think they’ll really appreciate it. I think they’ll really enjoy being able to do whatever it is they think is fun, and it’ll kind of work. That’ll help reach a broader audience, and I really want to reach that broader audience. Everybody knows Mickey, everybody loves Mickey—he’s a great hero for nongamers to embrace.

Q: Do you think it’s fair to say that a lot of people really don’t know Mickey though? For a while, he’s kind of languished and just become a sterile mascot.

Spector: You can characterize it any way you want, but I think it’s undeniable that Mickey is if not the most recognizable he’s one of the most recognizable icons that we have worldwide. One of the other things that really appealed to me about this is that you don’t get the opportunity to work with an icon very often. And it’s a real honor to be able to do that. I think in terms of recognizability, he’s huge. In terms of popularity, he’s huge. When you open up the pages of People magazine and see starlets wearing Disney couture, there’s still a cool factor there in a weird sort of way. But what we haven’t seen for a long time is Mickey as the star of a story, as the hero of an adventure. I’ve only been working with Disney for a little while, so I can’t speak to why that is, but I think it was kind of a conscious decision. Disney historically has rested properties, and there hasn’t been a Mickey game since 2003 or 2004 maybe. It’s just a question of this is the right property and the right time to bring him back. With the appeal of the Wii, the appeal of characters like Mario and Sonic and Kirby, it seems like the time is right, it seems like the platform is right—I certainly am not comfortable saying that this is a guaranteed success, but I think I’m the right guy to make the game. I think we’ve got the right story. I think all we’re trying to do is make Mickey a video-game hero, and I think we can do a pretty good job of that.

Q: It seems like there’s something about Mickey that makes him a good choice to revive. What do you think that might be? What’s Mickey’s core?

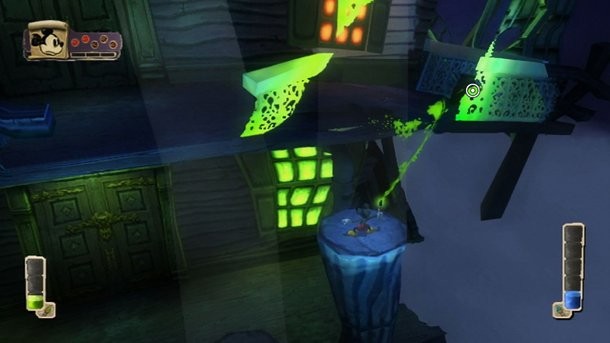

Spector: Mickey does have a core—you almost answered the question yourself. When you’re working with any licensed property or any existing property or any existing character, your first obligation is to identify the heart of the character. What’s the core? Why has Mickey stuck around for 82 years? How many things from 1928 have any relevance to our lives today? Let’s see…none. I think it’s literally true. There’s almost nothing in the mass media from 1928 that has any relevance. How many people are reading Philo Vance mysteries from S.S. Van Dine? How many people are watching ‘The Love Trap,’ featuring Laura La Plante? There’s very little from that era that has any relevance to us today at all. Mickey has that. The first thing that you have to do is find what is that. Why is he still around? It’s partly because I think Disney is very creative in updating and changing him and knowing when to rest him—saying, ‘OK, let’s let him sleep for a little while.’ But also, there is a heart to this character. There are consistent things, whether he’s on television or in theme parks or Fantasia or Steamboat Willie. Wherever he is, he’s smart, he’s loyal, he’s a friend to everyone, he never gives up. He also is overly enthusiastic—he doesn’t always think before he acts. And he’s mischievous; he’s always been a mischievous little guy. If you take all those things together, that’s kind of the starting point for a really good video game character. What I wanted to do is make sure we captured that, and then bring in some other elements, like the ability to use paint and thinner, to draw and erase. What does it mean to be a cartoon character? Well, it means you’re not real. You’re made of paint. As long as we were true to that core, we could layer in those other abilities and those other characteristics that could make him even more effective and appealing as a video game character.

Q: Mickey is absolutely one of the most recognizable characters, and I know people are familiar with him as a character at the theme parks and as a mascot, but with his older cartoons he was really funny, too. I think that aspect of him has been lost over the years, and Epic Mickey seems to be attempting to restore that.

Spector: It’s funny. Everybody thinks, ‘The guy who did Deus Ex and all of those Ultima games, what is he doing making a cartoon game?’ In the tabletop game world, I was the funny guy. It’s crazy. I did Toon, the cartoon role-playing game, I did Bullwinkle and Rocky the party role-playing game, I wrote my master’s thesis on cartoons—I was the funny guy. It’s just that there wasn’t much room for funny in the computer-game business, so I was doing other stuff. But now I get to express this other side of my personality. This one’s pretty funny I think, and there’s adult humor and kid humor. I’m trying to reach everyone who owns a Wii, which is pretty much everybody.

Q: There’s an element of the game changing whether you’re good or bad, or nice or destructive…

Spector: It’s easy to misinterpret the idea of choice and consequence, so I have to be really clear about this. In all of my games, including this one, I try not to judge. Most of the games about choice and consequence—and thankfully there are a lot of them now. When I started doing this, nobody else was doing it. It was me and Richard Garriott and some guys at Looking Glass, and we felt like, ‘Hey, we’re here, we’re doing cool stuff!’ But now, everybody’s doing it. But most of the games with choice and consequence, it’s like there’s a meter somewhere, and you can move it all the way to the good side or all the way to the bad side or all the way to the light side, all the way to the dark side. You can be right or you can be wrong. I think that’s missing the boat a little bit. I don’t like to judge.

In Deus Ex, you could kill everything that moved or kill nothing. Either way, you’re the hero and you’re saving the world. There are a bunch of ways to solve problems. In this game, it’s not that drawing is good and erasing is bad—an artist draws something and there’s a mistake or something that they don’t feel is quite good enough, and they erase it, and then they draw something else. Is that evil? Well, no. So it’s really just about what kind of hero your are. Frankly, what do you think is fun? It has nothing to do with good or evil. There’s no morality system in the game. It’s just about different choices, with different rewards, and different consequences. Anybody who would make Mickey Mouse evil probably doesn’t deserve to make a Mickey Mouse game. That’s probably not what it’s about. It’s important to be clear about that. It’s not good and evil, it’s not right and wrong.

Q: When the guys got back from the cover trip, they were like, ‘Whoh, Warren is really into Mickey Mouse.’ Maybe this is an artificial construct, but it seems that with animated characters, there’s sort of a Beatles/Stones thing between Mickey and Disney versus some of the other mascots and animation studios from that early era. Why did you fall on the Disney side of things when you were a kid?

Spector: When you sit around on Sunday nights watching the Wonderful World of Disney lit by the phosphor dots of you black and white television, it’s hard not to embrace the character. Walt and Mickey were part of my family. That was an important part of my childhood. And I think that’s true for everybody—even people who claim to not like Mickey Mouse, not that there are any of those in the world, of course, they still have that somewhere in their hearts a little three-circle place.

Q: Is it fun to think that soon there will be families illuminated by their plasma TVs enjoying Epic Mickey?

Spector: I have this picture in my head of a family sitting on a couch together, a little 9-year-old kid playing the game and then dad starts laughing at something and the kid goes, ‘What are you laughing at?’ There’s humor for both of them. And then he says, ‘Dad, will you go fight that boss for me?’ and hands over the controller and dad fights the boss. I really would love it if at 2 in the morning the dad wakes up, sneaks into the living room, and starts playing the game. I was really inspired when I went to see Enchanted, the Disney movie from a couple of years ago. Just sitting in the theater, me and my middle-aged wife. [laughs] I should not have said that. My wife and I are a middle-aged couple. We are. Let’s face it. We’re young at heart. I am dead, oh my god. [laughs] Anyway, but there’s a family of four sitting in front of us with young kids, a single dad with a kid, an elderly couple behind us, and everybody is enjoying Enchanted, together but differently. I think that’s what makes the Pixar movies special, I think that’s what Walt’s ideal was, awakening the child in every adult. I think more games could do that. I’m at a point in my life and in my career where I would rather do that than reach 18- to 34-year-old males with ‘I wear sunglasses at night’ characters. This is an interesting, different challenge.

Q: It seems as though there aren’t so many developers taking chances like you seem to be doing…

Spector: I don’t know that I’d characterize it that way. I’m not going to wax too philosophical, I’m going to try to keep it short, but I think we’re actually living in somewhat of a golden age in games right now. People ask me ‘What’s the coolest thing you’ve seen in games recently?’ and my answer is always a nonanswer. The coolest thing is that everything is happening in games right now. There are iPhone games and iPad games and DS games and MMOs and casual Facebook games and social games that are barely games, there are console games—there are so many ways to reach an audience and so many different audiences to reach, and so many different scales at which you can work. It’s crazy—crazy good. I think there’s plenty of innovation. It may not be happening in the mainstream triple A console game space, which may be where you’re thinking, but even there the fact that I can point to half a dozen major developers who are making games that are more about empowering players than about showing off how creative designers are—the fact that there are half a dozen, maybe more, even that says, ‘OK, we’re pretty healthy right now.’ I’m feeling pretty psyched about games right now.

Q: What kinds of design considerations come alongside developing a game for a wider audience, aside from obvious things regarding content?

Spector: I’ve always felt that I’ve always had a little bit of an advantage there in that I’m not making a shooter, where if you’re not good enough you have to stop playing, or a puzzle game where if you’re not clever enough you have no choice but to stop playing. In all of my games, I’ve tried to make it where if one approach doesn’t work you can try another. In this game we’re doing a lot of blind testing. You watch a kid play, and they get out the thinner and erasing everything and running around and having a good time, ignoring the story. And then you watch someone a little older—sometimes it’s the difference between a 9-year-old and a 12-year-old, it doesn’t have to be a huge gap—they’ll stop and discover a lactose-intolerant cow, for example. And one of the ways they can solve the problem is by giving her some ice cream, but that’s probably not a good idea because she’s lactose intolerant. ‘It might be a little harder to go find this other solution to the problem than to give her some ice cream, but I know I should do that.’ There are layers in which the game works, both in terms of how you do puzzles, but also in how the humor comes through. Games that offer players options and problems rather than puzzles have an advantage. I’ll be frank—sometimes it’s a little bit harder to solve problems using paint and being friendly and doing all the side quests that will get you information that helps, but that might be more satisfying to some people.

Q: As a fan of Disney, were there elements that you tried to fit into the game that you just weren’t able to, and was there anything that you did get into Epic Mickey that was a particular triumph?

Spector: Well, there’s always stuff you don’t have room for. I’m kind of a kitchen sink designer, where I throw everything in and then I start pulling things out that don’t fit anymore. I really wanted to do an Alice in Wonderland-inspired world, but I talked to Disney—and it was partly my choice and partly theirs—and they said, ‘This probably isn’t a great idea, Tim Burton’s Alice is coming out, why confuse people?’ I wanted to do a bunch of stuff with fairies, and that ended up not fitting, because we had the gremlins, who were kind of similar in function.

The thing I’m happiest about, I guess, is Oswald. We’re just introducing Oswald here, and it’s the first time he’s been in a new Disney story since 1928. He was Walt’s first cartoon star. There is a moment in the game that will the first time since we’ve seen Oswald on the screen in a new Disney story for more than 80 years. I'm not kidding when I saw I tear up and swell with pride that we’re the people that get to put Oswald on the screen for the first time ever in terms of your life and my life. Holy cow. That’s a thrill. Oswald and the gremlins, there should be games about those guys. They don’t need to be co-stars, they need to be stars.